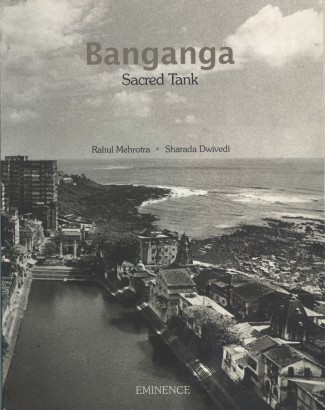

Book

Baganga – Sacred Tank

A story is told in the Skanda Purana about Parashuram, sixth avatar (incarnation) of Vishnu, who killed the Kshatriya race and donated all land on earth to the sage Kashyap Muni, leaving himself no place to accomplish tapasya (penance). Standing atop the Sahyadri mountains, Parashuram persuaded Sagara, the ocean, to recede some distance. A long belt of land was thus created, west of the Sahyadri mountain range and stretching along the western coast of India from Kanyakumari in the south to Bharuch in the north and named Parashuram Kshetra.

The Skanda Purana asserts that in this new region the most sacred tirthasthana or centre of pilgrimage was Valukesho Mahashreshttho Banganga Saraswati or the holy Banganga at Valukeshwar in Maharashtra. This tank of Banganga in Bombay is perhaps the oldest and largest surviving Hindu tirthasthana on the island city, dating as it does in its present form to the early 18th century. Its earlier avatar, in fact, goes back much further to the era between the 9th and 13th centuries AD. What is even more astonishing is the fact that the myths and legends associated with the tank and the adjoining Walkeshwar temple complex emanate from the age-old Skanda Purana and further back from the epic Ramayan, which is believed to have been written about three centuries before the birth of Christ.

Today, the stepped tank called Banganga, surrounded by temples, samadhis (memorials), matths (hermitages), dharmashalas(pilgrims rest-houses) and residences, stands on the western fringes of Malabar Hill, close to the Government House estate at Malabar Point. Over the decades, and particularly since the intensive development of Malabar Hill beginning from the 1960s, this tranquil, historic centre of pilgrimage has been severely transformed by being virtually engulfed by haphazard highrise development in the environs.

In this book, we present the history legends of Banganga in the context of the development of Malabar Hill. We have also included a parikrama route, a walking tour around the Banganga complex, where important sites and the present (1995) state of the place have been described. In addition to written sources from manuscripts, books and newspapers, our research relies considerably on oral history, a tradition that has tenaciously endured in India. This source of history has its strengths, in that knowledge that would otherwise be lost is recorded for posterity, but it also has weaknesses in the fact that oral accounts are sometimes distorted, flavoured as they are with spice and exaggeration. But that’s how myths and legends are often born.